Introduction

It seems western commentators can always find something to worry about regarding China. Last year it was shadow banking and the property market. Lately it’s been the sharp rise and pullback in its share market. The latter has indeed been severe – with a 32% fall over 3 and a half weeks. There have been many headlines regarding the share market volatility and efforts to stabilise the market. This note looks at the key issues.

Chinese shares – what happened?

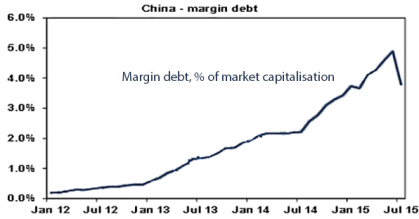

Starting about a year ago the Chinese share market commenced a new bull market after the bear market that began in August 2009 came to an end. This made sense as Chinese shares were amongst the world’s cheapest and the Chinese authorities were gradually starting to ease economic policy. But as the market moved higher, expanding margin debt (ie buying shares using debt) helped accentuate the gains into its June 12 high. Since then to its low point last week the Chinese share market (as measured by the Shanghai Composite) had a fall of 32%. Essentially there have been three drivers of the pullback:

-

Regulatory measures to stabilise the market – Chinese authorities tried to slow it down with tighter margin regulations and an increase in capital raisings (or initial public offerings (IPOs)).

-

This started to bite last month at a time when shares had become overbought after a 150% gain over 12 months and ripe for profit taking.

-

Just as the increased use of leverage via margin loans accentuated the upside, the unwinding of such positions – often triggered by margin calls as shares fell in value – appears to have accentuated the downside. As the pressure to unwind geared positions increased while the market fell, it made the decline somewhat self-reinforcing. From the high, total margin debt looks to have fallen by around 30%, which has taken it back to levels seen early this year.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

Government moves to stabilise the market

As the downturn accelerated, there were concerns it could destabilise the financial system and economy. So Chinese authorities took a number of measures to stabilise and support the market. These included: lower interest rates; relaxed rules around margin financing; a suspension of IPOs; a fund to buy shares set up by major stock brokers; investigations into short selling; the provision of liquidity by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) to the China Securities Finance Corp, effectively enabling it to buy shares; various orders & commitments not to sell shares; and a ban on shareholders who own more than 5% of a company and insiders from selling the shares for six months. These measures have started to help, with the Shanghai Composite up 13% from its low.

What are the implications for the Chinese economy?

While the significant drop in Chinese share values is unsettling for some investors, the impact on the Chinese economy is likely to be limited:

-

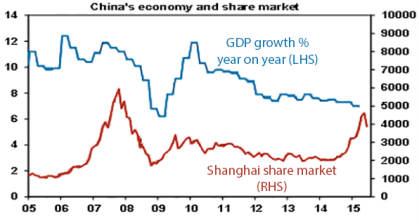

The 150% 12-month gain in Chinese shares to the high had limited economic impact so it’s hard to see why the fall will.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

-

Second, Chinese shares are still up 90% from a year ago.

-

Third, shares represent only around 12% of total household wealth in China so the wealth effect on spending is limited.

-

Fourth, any systemic impact on the Chinese financial system is likely to be minor. Stock brokers and mutual funds are only 5% or so of total financial system assets and any negative effects will be offset by PBOC liquidity measures.

-

Finally, equity financing is only a very small share of total financing – just 4% – with bank financing dominating.

Comparisons between China’s recent share market fall and the 1929 stock market dive in the US make entertaining headlines but are wide off the mark. The US share market boom of the 1920s went hand in hand with a booming economy whereas the bull market in Chinese shares only started a year ago, the economy has been slowing since last decade and the severity of the 1929-32 85% plunge in US shares and associated economic depression owed more to policy mistakes at the time such as initially tightening monetary and fiscal policies – mistakes that the Chinese authorities are not repeating. A better analogy might be 1987 where shares in the US, Australia, etc, surged, plunged and then resumed their rising trend without any significant economic impact.

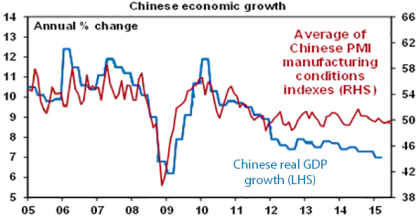

In a broader sense, after a soft start to the year, Chinese economic growth has slowed to around 7%. With business conditions PMIs tracking sideways it looks like remaining around this level or maybe just a bit below. For the reasons stated above we don’t see the share market set back significantly impacting this.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

More broadly, there are some positive signs beyond the share market turmoil supporting the view that Chinese growth will still come in “around 7%” this year:,/p>

-

The PBOC has now been easing monetary policy. With inflation running well below the Government’s target, there is still a need for further monetary easing (as real lending rates remain very high). This is likely with the 12-month benchmark lending rate likely to fall below 4% by year end.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

-

Second, major spending programs around various infrastructure projects are starting to get rolled out as the focus has shifted back to maintaining growth.

-

Third, the risks around the Chinese property market appear to be fading with price declines giving way to modest gains.

Implications for the global and Australian economies

With the share market fall in China unlikely to have a major impact on Chinese economic growth, it’s hard to see a huge impact on the global or Australian economies. However, Chinese growth around 7% is still a long way from the 10% plus seen last decade. At a time when the supply of commodities is continuing to ramp up, the secular trend in commodity prices is likely to remain down. So the risks to the iron ore price and Australia’s terms of trade remain on the downside.

Longer term reform prospects

While some have questioned the Chinese government’s intervention in its share market, it needs to be recognised that the intervention is not unique. The Hong Kong Monetary Authority bought HK shares in 1998 in a move that helped end the Asian crisis. The Bank of Japan is buying Japanese Real Estate Investment Trusts and Exchange Traded Funds as part of its quantitative easing (QE) program. And western central banks QE programs have helped support their share markets in recent years. This shouldn’t be seen as negative but rather a sensible response to prevent broader instability.

Also, reform is not a straight line in China but rather very pragmatic. This is just as well. Surely, after problems emerge, it’s better to back track a bit on reforms, learn from mistakes (for example to get margin lending under control) and then proceed again. Better that than let a systemic blow up unfold!

So what does all this mean for Chinese shares?

Some commentators have expressed concerns that the Chinese share market became a giant bubble. To be sure, it rose too fast from a year ago and valuations of small caps became excessive. For example, the price to earnings multiple of the small cap-dominated Shenzhen stock exchange rose to around 80 times. However, for large caps (which dominate the Shanghai exchange) valuations were less extreme. For example, the Citic 300 share price index (basically the top 300 stocks) saw its PE rise to around 22 times. It’s now back to around 17 times, which is well below the long-term average of 28 times and the forward PE has fallen to 14.7 times which is cheaper than Australia.

Source: Thomson Reuters, AMP Capital

Meanwhile, Chinese companies listed in Hong Kong have also been caught up in the recent correction and represent particularly good value at around 8 times forward earnings. Apart from reasonable valuations, both mainland and Hong Kong-listed Chinese shares will benefit from monetary easing.

Yes, it may take some time for some investors to fully get their confidence back but there have been numerous sharp falls in share markets throughout history only for share markets to resume their rising trend over time. And China’s share market is unlikely to be any different.

About the Author

Dr Shane Oliver, Head of Investment Strategy and Economics and Chief Economist at AMP Capital is responsible for AMP Capital’s diversified investment funds. He also provides economic forecasts and analysis of key variables and issues affecting, or likely to affect, all asset markets.

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this article, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591, AFSL 232497) and AMP Capital Funds Management Limited (ABN 15 159 557 721, AFSL 426455) makes no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This article has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this article, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This article is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.