Introduction

Tax reform is a hot topic in Australia with lots of strongly-held views. There are three main reasons. First, despite the tax reforms of the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s the Australian tax system is still far from ideal. This is highlighted by the Government’s Tax Discussion Paper. Second, some see tax reform as a way to plug the budget deficit; in other words tax reform is actually a euphemism for boosting the tax take. Third, some see various aspects of the tax system as being significant causes of problems in the economy.

Four “tax concessions” in particular seem to be readily in the headlines: negative gearing, the capital gains tax discount, franking credits and superannuation. The common arguments put up for curtailing them are that they cost the Government revenue, create distortions in the tax system and hence in economic and financial activity, and that their dollar benefits fall disproportionately to high-income earners. This note takes a look at each of these and points out that they really need to be seen in the context of the overall income tax system.

Negative gearing

Every time Australian residential property prices take off, calls erupt for negative gearing on investment property to be restricted or scrapped as many see it as being to blame for high house prices. Such a move would clearly adversely affect property investors as it will effectively reduce the amount investors can borrow. However, such a move is of dubious merit from a range of perspectives.

First, negative gearing is not the reason housing affordability is so poor in Australia. It has been in place for a long time and Australia is not alone in providing some form of “tax assistance” to home owners as most comparable countries do. Americans can even deduct interest on the family home from their taxable income. And yet our house price-to-income ratios are much higher.

Removing or curtailing negative gearing could even make the situation worse by reducing the supply of rental accommodation at a time when rental yields are hardly attractive for investors.

Rather, the real driver of poor housing affordability has been a lack of supply. In a well-functioning market when demand goes up, prices rise and this eventually is met with increased supply. Residential construction is now picking up, but this follows more than a decade of undersupply that has to be made up. What we really need to do is to make it easier to bring new homes to the market – release land for development faster, relax (within reason) development controls, reduce tax and other impediments to the supply of new dwellings and develop a long-term plan to decentralise away from our major cities. This would be the best way to help first home buyers and cool speculative interest in housing. Curtailing negative gearing is not the solution.

Second, removing or restricting the deductibility of interest expenses incurred in property investment will cause a distortion in the tax system. As the Tax Discussion Paper points out, negative gearing is not actually a tax concession specific to property investment, but arises because of the way the tax system works in allowing deductions for expenses incurred in earning income. So removing or curtailing the tax deductibility for interest costs incurred in property investment will create a distortion in the tax system as it will still be available for investment in other assets. As a result, the tax system would then have a bias against property and in favour of assets like shares.

Finally, while the dollar value of negative gearing rises with income levels (which is to be expected) the majority of tax payers that negatively gear property (around 650,000 people) are actually middle-income earners.

The capital gains tax discount

The capital gains tax discount was introduced in 1999, allowing investors to halve their taxable capital gain on an asset provided they hold it for more than a year. This was arguably a simpler arrangement than the prior approach of allowing capital gains to be adjusted for price inflation and has the effect of encouraging somewhat longer-term investment horizons. Against this, though, it may be argued that the discount is excessive particularly when inflation is low and that it therefore provides an inducement to earn income as a capital gain as it’s taxed at half the rate and that one year is not really long enough to encourage long-term investing.

In fact, it’s arguably the capital gains tax discount that distorts investment flows into residential property as opposed to negative gearing. This is because when negatively gearing an asset an investor is realising loss year to year in the hope that the capital gain on sale will ensure that the investment ultimately generates a decent positive return. Paying tax on only 50% of the capital gain therefore helps make this stack up.

So in this sense, there is a case to consider removing the capital gains tax discount and returning to the pre-1999 approach of adjusting the capital gain to be included in taxable income for price inflation.

Dividend Imputation

The dividend imputation system introduced in 1987 basically gives a tax credit to Australian investors for tax already paid on company profits when they are distributed as dividends. However, both the Financial System Inquiry and the Tax Discussion Paper have questioned the merits of the system. Commonly-expressed concerns are that it creates a bias for Australian investors to invest in domestic equities, adversely affects the development of the corporate bond market, may encourage firms to pay out too much of their earnings rather than invest them and that approaches used by other countries seek a similar outcome but may come with lower compliance costs.

Most of these concerns are misplaced, though, and ignore the benefits of the imputation system:

First, dividend imputation actually corrects a bias against equities by removing the double taxation of earnings – once in the hands of companies and again in the hands of investors as dividends. Therefore, it actually puts shares onto a level footing with, say, a corporate debt investment.

Second, flowing from this, it means that the cost of equity capital to firms is not penalised (ie pushed up) relative to the cost of debt capital so it has reduced the incentive of Australian firms to excessively rely on debt financing. This stands in contrast to, say, US companies that are incentivised to borrow and buy back shares.

Third, it also encourages corporates to pay decent dividends to shareholders as opposed to irrationally hoard earnings. The higher payout ratio of Australian companies has led to superior capital discipline within companies and a superior capital allocation between them as it has put power back in the hands of shareholders who can then decide whether dividend reinvestment plans warrant their participation. It has certainly not hampered the long-term returns from the Australian share market. Since dividend imputation was introduced in 1987, Australian shares have returned 10% pa compared to 7.4% pa for global shares (in local currency terms).

Fourth, dividend imputation removes a bias for private business owners to stay unincorporated to avoid getting taxed twice on their profits.

Finally, while franking credits create a bias for Australian shareholders in favour of Australian shares over global shares where franking does not exist, this is not an argument to return to the double taxation of dividends.

While better alternatives to dividend imputation may be worth considering if they exist, the system has served Australia well and so there is a very strong case to retain it. It should also be recognised that franking credits add nearly 1.5% pa to the return from Australian shares, so removing them will cut into the investment returns and hence retirement savings of Australian investors.

Superannuation concessions

Superannuation contributions, earnings and benefits to those over 60 are taxed concessionally because saving through super is compulsory and the savings are “locked up” for use in retirement. Apart from the benefit to the economy from having a large pool of patient capital keen on investing in Australia, the aim of compulsory superannuation was to improve retirement incomes and reduce reliance on the age pension. With just 30% of people of age pension age being self-funded, and this not projected to decline by 2050, some have questioned whether the superannuation system is working. Of course, it’s not quite so bad as the proportion getting a part pension relative to full rate pensioners is expected to increase. But still the question remains as to whether more can be done to ensure that retirees rely on accumulated superannuation funds before accessing the pension, as opposed to viewing superannuation as being for wealth generation and funding bequests. The move by the Government to reduce the asset threshold for accessing the pension is partly aimed at this.

More broadly, a common criticism of superannuation is that the rules around super are regularly changing and this generates uncertainty. It can be seen in the Westpac – Melbourne Institute Consumer survey finding that despite the tax concessions only 5.2% of surveyed Australians regard super as the wisest place for savings, well behind bank deposits, real estate, paying down debt and shares. So any future changes need to allow for this and ideally have a long phase-in time so those who have acted within the current rules don’t feel hit by overnight changes.

The overall tax system

Finally, and very importantly, calls to end or curtail these “tax concessions” need to be assessed in the context of the whole individual income tax system. Australia already has a relatively high reliance on income tax and the current top marginal tax rate at 49% is above the median of comparable countries (and compares to 15% in Hong Kong, 20% in Singapore and 33% in New Zealand) and kicks in at a relatively low multiple of average weekly earnings of 2.3 times – compared to 4.2 times in the UK and 8.5 times in the US. This gets a tick in terms of fairness but could be working against Australia’s long-term interest to the extent that it discourages work effort and hence productivity.

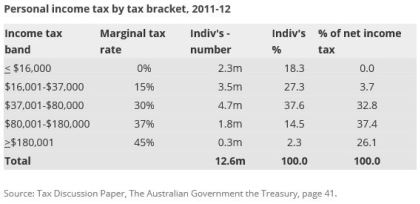

As a result, the Australian individual tax system is highly progressive and this is reflected in the fact that in 2011-12 just over 2% of taxpayers accounted for 26% of income tax revenue and just less than 17% of taxpayers accounted for over 63% of income tax revenue. This is likely to have become even more skewed since then due to the Budget Repair Levy.

Curtailing access to any or all of the “tax concessions” mentioned earlier will only add to the burden on this relatively small group and act as a disincentive for work effort at a time when we should be doing the opposite. Ideally, we should be looking to reduce the reliance on income tax. If we did this the interest in strategies like negative gearing would likely decline.

About the Author

Dr Shane Oliver, Head of Investment Strategy and Economics and Chief Economist at AMP Capital is responsible for AMP Capital’s diversified investment funds. He also provides economic forecasts and analysis of key variables and issues affecting, or likely to affect, all asset markets.

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this article, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591, AFSL 232497) and AMP Capital Funds Management Limited (ABN 15 159 557 721, AFSL 426455) makes no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This article has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this article, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This article is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.