Introduction

It’s now coming up to six years since Greece first revealed that it had understated its true level of public debt. And this is the fourth year in which it has seemingly held global financial markets to ransom as a result of its excessive public debt level. To be honest it’s becoming a bit of a drag. Greece should never have made it into the Euro, but of course getting it out again is easier said than done. Greece is now rapidly approaching another moment of truth, and this has been causing increasing angst in investment markets with the risk of more to come. This note looks at the key issues.

What is the current state of negotiations?

In February Greece and its creditors (the IMF, EU and ECB) agreed to extend its current bailout program to end June. Since then the two sides have been negotiating the release of €7.2bn of funds under that program. Negotiations have not gone well with Greece’s new Syriza led Government hoping to extract something more favourable. The size of the targeted primary budget surplus (ie the surplus excluding interest payments), pension and labour reforms have been sticking points along with Greece’s desire for a reduction in its debt level.

Greece is now coming up to a crunch point as it needs to make a payment to the IMF of €1.5bn by June 30. It will also have trouble paying pensions and public servants through July and is due a €3.5bn payment to the ECB on July 20. So it’s become urgent that funds are released under the current bailout program. Similarly at the end of June Greece’s loan program expires and it is easier to negotiate a new one in the context of this one rather than starting all over again.

Developments in the last few days have been positive with a new proposal from Greece representing a significant move towards the position of the creditors in terms of pensions, tax, spending and the budget. It has been greeted positively by European officials and leaders so there is now a good chance a deal will be agreed this week at a European leaders’ summit, albeit there is still more work to do which could upset this and cause bouts of market volatility. And then it will have to pass various parliaments starting with Greece. The latter could prove interesting as some Syriza parliamentarians may not support it so the Government may have to rely on other moderate parties.

While the June 30 IMF payment is the next key date to watch, there is probably still a bit more time into July. An actual default will not come till the IMF writes a letter informing Greece it’s in default. Furthermore, if an agreement is reached but it’s not all signed sealed and delivered in time for the June 30 payment the creditors may simply agree to delay payment until any necessary parliamentary votes and referendums occur.

Why has a deal taken so long?

The negotiations on a “reform for funding” deal for Greece have been long and acrimonious for several reasons. On the Greek side: Syriza was elected on an anti-austerity, anti-reform mandate and it’s likely that its more radical members could quickly desert the Government if a deal gives away too much. The new Government is also very inexperienced and more prone to belligerence that the European way of compromise.

For the Eurozone: being too lax with Greece is seen as just as risky as being too tough. This is because giving in too easily could embolden support for the populist party Podemos in Spain and similar parties elsewhere which would in turn threaten reforms designed to bring about convergence in the Eurozone and so weaken its medium term stability.

Is a deal still likely?

Despite this our assessment is that a deal is more likely than not for the simple reason that it’s in in the interest of both sides to reach agreement. For Greece it’s to avoid the economic mayhem that would follow default and a forced exit which would include a banking crisis and associated credit crunch, a huge loss of confidence, further austerity as a rising budget deficit forces more aggressive spending cuts and a likely 50% or so collapse in the new currency Greece adopts. With 70% or so of the Greek population wanting to remain in the Euro such an outcome would likely lead to the demise of the Government led by Tsipras and Syriza.

For the creditors the reasons to reach a deal are to preserve their roughly €300bn exposure to Greece, to head off any blow to confidence and perceived threat to other peripheral countries via “contagion” and to avoid the perception that membership of the Euro is reversible which could weaken integration long term.

In this regard, the war of words around Greece that escalated last week is very similar to that amongst US politicians ahead of its various debt ceiling deadlines, all of which ended in a deal. So our assessment remains that a deal will be reached and the positive developments seen so far this week are consistent with that. Once Greece actually signs up and starts delivering on reforms some form of debt relief is likely to be offered.

What is the problem with Greek banks?

With uncertainly running high in Greece, its citizens naturally fear they will wake up one day and their Euro bank deposits will have been redenominated into a new Drachma worth 50% less. So they have been taking their money out in droves with the outflows escalating to around €1bn/day lately. So the banks have been relying on emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) from the ECB. However, if there is no deal the ECB may curtail or cut this off. This in turn would likely force the closure of Greek banks and the imposition of controls on withdrawals. Which in turn would likely set off a credit crunch. All of which is further increasing the pressure on the Greek Government.

What if there is no deal? Will default lead to Grexit?

If there is no deal Greece will not be able to meet its June 30 IMF payment and if no deal is in prospect, Greece will be declared to be in default sometime in July. There would be two scenarios here: default but no exit from the Euro; or default leading to Grexit. Just because Greece defaults would not automatically mean that it will leave the Euro. Much would depend on how supportive the ECB would be of Greek banks after a default. Any continued support though may be limited and this plus the loss of confidence and the likely downwards spiral of the Greek economy would likely add pressure on the Greek Government to sign up to a deal.

But if ECB support for Greek banks evaporates and no deal eventuates then in order to avoid even more aggressive austerity and support its banks Greece may decide that it needs to start printing its own money. Since it can’t do this in the Euro it would have to exit. This may take several months to unfold and it could be very disorderly which would be bad for financial markets in the interim and be very bad for stability in Greece.

What is the risk of contagion if there is no deal?

The risk of a contagion if Greece defaults like that seen in the Global Financial Crisis where financial institutions stopped lending to each other because of fear that the counterparty might be exposed to sub-prime debt or Lehmans or whatever resulting in a freezing up of global lending markets is very low. After various debt haircuts private sector exposure to Greek public debt is very low at around €50bn with more than 80% of Greek public debt held by the EU, ECB and IMF and after more than five years the risks are well known. And because private ownership of Greek debt is so small Greece may not default on this preferring to try and keep potential access to the private markets open. Of course, this does not mean a hedge fund does not have a leveraged position but the risks are low.

Rather the main concern is that a Greek default followed by an exit from the Euro prompts investors to look for other countries that may follow suite leading to a contagion which could become self-fulfilling. This is what started to happen in 2010-12 till the ECB put an end to it with President Mario Draghi’s commitment to do “whatever it takes” to keep the Euro together. The risks are clearly there, but there are several reasons to believe the risks are now low. First, peripheral Europe is now in far better shape than was the case in 2010-12.

-

Portugal and Ireland are now both off bailout support.

-

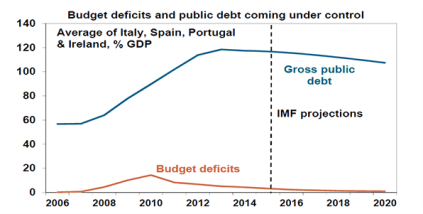

Budget deficits are coming under control in Portugal, Ireland, Spain & Italy. The average deficit in these countries was around 4% of GDP in 2014, versus 14% in 2010. This is set to see average public debt levels fall this year.

Source: IMF, AMP Capital

-

Economic reform has been underway. One guide is unit labour costs which reflect productivity growth and labour costs. Spain and Portugal have made significant progress in cutting costs relative to Germany.

-

Another guide is the ease of doing business. The ranking of peripheral countries relative to Germany in the World Bank’s Doing Business Survey has improved significantly. Eg, Spain has gone from 38 countries behind Germany to 19.

Second, defence mechanisms to support troubled countries are also stronger with a strong bailout fund, a banking union and a more aggressive ECB. The ECB’s €60bn/month in debt purchases and the threat of buying individual country bonds (under its Outright Monetary Transactions program) should help keep bond yields in peripheral countries from being pushed too far away from levels in Germany. To this end it’s noteworthy that 10 year bond yields in Spain and Italy at around 2.2% are a long way from the 7% plus level they reached in 2012.

What is the relevance to Australia?

Greece is only 0.25% of global GDP and a trivial market for Australian exports. So the direct impact on Australia is virtually non-existent. Rather the relevance comes via Greece’s membership of the Eurozone and its potential to de-stabilise it and hence European economic growth. And here the impact is via investor sentiment and hence share market volatility and also via China since Europe is China’s biggest export market.

What about Eurozone assets?

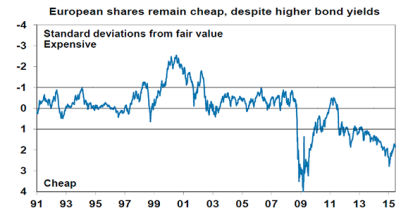

A “reform for funding” deal that avoids a real default and at the same time does not bend over so much to Syriza that it emboldens Podemos in Spain would likely be greeted positively by Eurozone shares and peripheral country bonds, as seen by the reaction this week to news that a deal is in prospect. By contrast a default leading to a Grexit would initially be taken badly. However, even here the fall out is likely to be limited as Eurozone shares are cheap and the ECB is now aggressively undertaking quantitative easing. In fact, financial markets might ultimately celebrate were Greece to leave the Euro.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

About the Author

Dr Shane Oliver, Head of Investment Strategy and Economics and Chief Economist at AMP Capital is responsible for AMP Capital’s diversified investment funds. He also provides economic forecasts and analysis of key variables and issues affecting, or likely to affect, all asset markets.

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this article, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591, AFSL 232497) and AMP Capital Funds Management Limited (ABN 15 159 557 721, AFSL 426455) makes no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This article has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this article, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This article is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.